Open-Source Internship opportunity by OpenGenus for programmers. Apply now.

Reading time: 40 minutes | Coding time: 5 minutes

In my last article, I have covered the basics of HTTP requests and the different ways to make requests using various ways in JavaScript. In this part, we will discuss HTTP requests in depth: how they work behind the scenes.

Before we delve deeper into this topic, let's see an overview of how the web works. When a person wants to visit a website, they type in the address of the site into their browser or client (for instance iq.opengenus.org). The web addresses typed into URL bars are not actual addresses of the sites. The actual web addresses are in the form of IP addresses (like 159.89.134.55). But memorizing these addresses is not convenient for each website a person wants to use.

This is why DNS (Domain Name System) servers exist. You can imagine these servers as the phone books of the Internet. Computers use IP addresses to identify and communicate with each other. When someone requests a website, the browser contacts a DNS server. The DNS server then tells the browser the IP address associated with the computer or server that hosts the requested site. This is the address of the device where the documents and files for that site are hosted. The files necessary get sent back to the browser and get assembled and rendered by the browser as the websites we use everyday.

Terminology

-

Client is the computer asking for service by making requests — e.g. to make a search or to check news

-

Server is the computer, that is usually located somewhere else, holding the things necessary to provide those services. It is responsible for sending responses to requests.

How actually are requests made?

Requests on the web are made through a set of steps and make use of a protocol known as HTTP. HTTP stands for HyperText Transfer Protocol. It is used for communication between the client and the server(s). It is the foundation of the Internet. HTTP uses the URL typed into the browser to identify the resource wanted and to make a connection.

When requesting a site, the URL looks something like this http://google.com. Using the URL provided, the browser identifies the request needs to be made through http and the domain name for the web address is google.com which it then sends to a DNS server to get the IP address of the server the site is hosted on. Once the client (browser) knows the IP address of the destination server, it opens a connection channel to it and makes the request needed. All this process is only the initial part of the steps taken to make the request.

Request messages are exchanged between the client and server to fulfill that request, and they usually follow a similar format. They contain 4 components: a start line, headers followed by an empty line to indicate the end of headers and an optional body.

Below is an example of a typical GET request message. This is similar to what you would usually see if you open the Network tab from your browser Dev Tools.

GET /tag/algorithm HTTP/1.1

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/73.0

Host: iq.opengenus.org

Accept-Language: en-us

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate

Connection: Keep-Alive

1. Start line

This is first line of a message where the general overview of a request or response is ---.

For a request, this line contains these values separated by a space: method, request URI and HTTP version followed by a new line.

- Method indicates the type of request to be made and common values include: GET, HEAD, POST, PUT, and DELETE.

- HTTP Version is the version of HTTP, usually HTTP/1.0 or HTTP/1.1.

- Request URI is the path to the resource upon which the request is to be made. It can be either an absolute URI or a relative URI.

Examples are shown below.

/- is a relative URI meaning root path. We are not navigating any further. We have identified the host, and we are making request on the root.

GET / HTTP/1.1

Host: iq.opengenus.org

https://iq.opengenus.org/tag/algorithm- is the absolute URI.

GET https://iq.opengenus.org/tag/algorithm HTTP/1.1

/tag/algorithm- is a relative URI meaning we are navigating to this path from the host or root path which is 'iq.opengenus.org'.

GET /tag/algorithm HTTP/1.1

Host: iq.opengenus.org

For a response, the template is composed of these values separated by a space: HTTP version, status code, and a reason phrase.

- HTTP Version is the version of HTTP, usually HTTP/1.0 or HTTP/1.1.

- Status Code is a 3 digit integer indicating the status of our response. These can be in any one of 5 classes:

- 100 - 199: Informational

- 200 - 299: Success

- 300 - 399: Redirection

- 400 - 499: Client Error

- 500 - 599: Server Error

- Status Phrase follows the status code and is a short summary of the status of the response.

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

HTTP/1.1 404 Not Found

2. Headers

Headers follow the start line, and they allow the client to pass additional information about the request or the client itself to the server, or they allow the server to pass additional information about the response to the client. They usually appear as key-value pairs. Headers can be:

- General headers - applicable to both requests and responses.

- Request headers - applicable to only requests sent by the client.

- Response headers - applicable to only responses sent by the server.

- Entity headers - applicable to message body (if there is any).

Some common headers are listed below.

| General | Request | Response | Entity |

|---|---|---|---|

cache-control |

accept |

age |

allow |

connection |

cookie |

location |

content-length |

date |

host |

retry-after |

expires |

upgrade |

user-agent |

server |

last-modified |

via |

DNT |

set-cookie |

content-type |

Header fields ensure requests and responses are made just the way the client and server want. In other words, header fields are a means of communication between a client and a server with specific details given to fulfill the request.

Caching is one method which makes this whole process more convenient for the devices involved. It improves performance by removing the need for a client to send any or some requests, or the need for a server to send back any or some responses. It does so by using the cache-control header field.

Content types are important in enforcing the data types sent to a server or sent back from a server are in alignment with each other. Header fields like accept and content-type are a means of communicating the types of files and documents involved in a request.

Client details like the type of hardware and versions of software are also important in delivering an optimized experience. The user-agent header field passes detailed information about the client to the server, so that the server can send back the necessary files for the request. Due to compatibility issues, the files necessary for a service to work on one device may be completely different from another device. Identifying device types using this header field helps the process.

3. Body

If our message has a body, it is preceded by an empty line which come after the headers. The empty line indicates the end of header fields. The message body carries actual data for a request from a client (e.g. form data when authenticating) or a response from a server (e.g. files and images).

A simple line of code can be passed after the empty line as the body of a request or a response. The following two examples show server responses: when the requested resource is found and when it's not found.

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Server: nginx

Content-Type: text/html

Connection: Closed

<html>

<body>

<h1>Hello, Friend!</h1>

<p>Nice to see you!</p>

</body>

</html>

HTTP/1.1 404 Not Found

Server: nginx

Content-Type: text/html

Connection: Closed

<html>

<body>

<h1>File Not Found</h1>

<p>Sorry friend, the requested resource wasn't found</p>

</body>

</html>

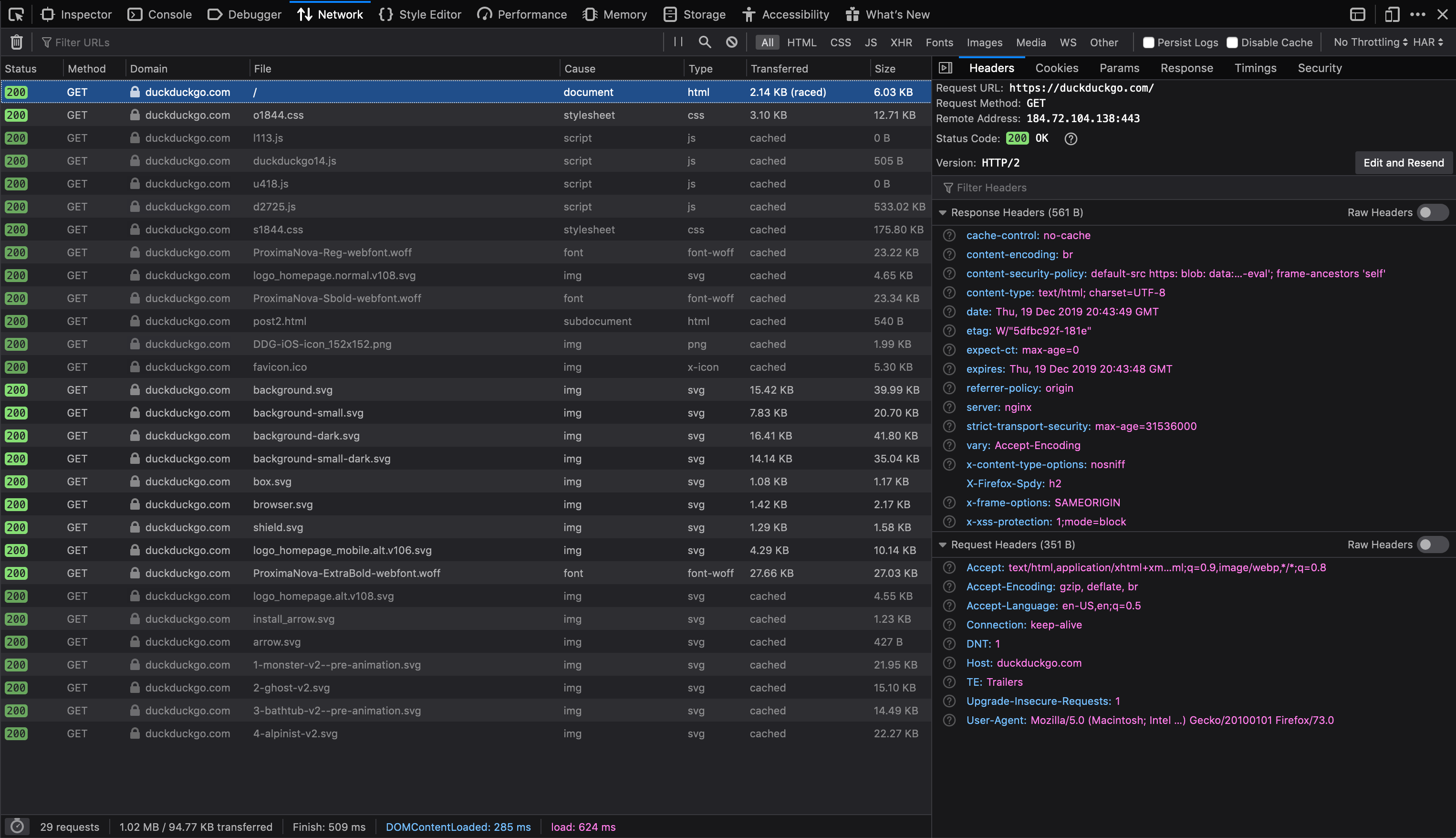

To get a closer look at requests in your browser, you can navigate to 'Network' tab of your browser's Developer Tools, or just hit Cmd + Opt + E on Mac or Ctrl + Shift + E on Windows and Linux. Type the URL to any website and see all the requests and responses made. Usually there are several requests and responses made. Each request fetching a single file that is a component of the website to be rendered.

The above image shows a detailed look at what goes on behind the scenes when navigating to the DuckDuckGo website. As you can see in the bottom left corner, there were a total of 29 GET requests made. File types range from simple HTML, CSS & JavaScript files to images and font files. Greyed out rows indicate the requests has been cached from previously made requests. The right section of the image shows the details of the first request which fetches the HTML file for the website. Consecutive rows show the order by which the other file types are loaded. When working with requests, it's important to make sure the necessary files come first. In this case, the HTML file is the most relevant file. For users whose connection might be interrupted easily, having the HTML file is enough to make the search. All the CSS, images and font files are secondary, and they're not really necessary for someone to make a search on DuckDuckGo.

A few more examples

In this one, we are using POST method to make searches on DuckDuckGo. The request looks like this:

POST https://duckduckgo.com HTTP/1.1

Accept: text/html

Accept-Language: en-US

Connection: keep-alive

Content-Length: 18

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/73.0

q=opengenus&t=ffab

PUT method is very similar to POST but it is used to update resources.

PUT /update.html HTTP/1.1

Host: website.com

Content-type: text/html

Content-length: 26

<p>File to be updated</p>

The DELETE method can be used to delete a given resource.

DELETE /resource.html HTTP/1.1

The server can send back a response notifying the client about the completion of the DELETE request.

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

<html>

<body>

<h1>Resource successfully deleted.</h1>

</body>

</html>

HTTPS

HTTP requests can be easily intercepted or read by anyone at some points in the network. Therefore, sensitive information like credit card numbers and passwords should never be delivered using HTTP. Instead, an extension of HTTP known as HTTPS (HyperText Transfer Protocol Secure) is used. It creates a secure channel over the network so that encrypted data is transferred between the client and the server. This provides protection from potential eavesdroppers man-in-the-middle attacks. This is one of the parameters your browser uses to notify you if a website is secure or not.